The Constitutionalism of Emergency and Contemporary Multi-level Systems

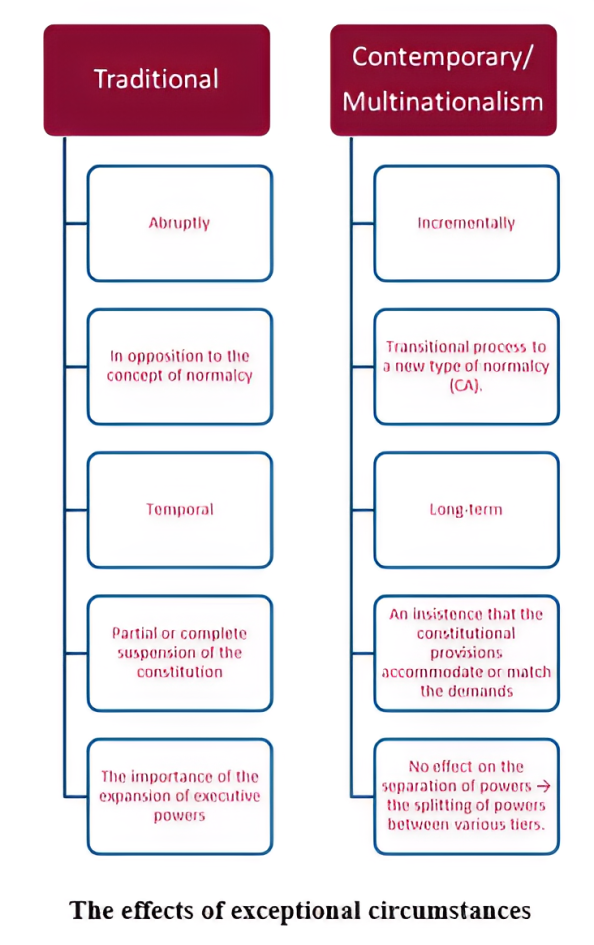

The majority of contemporary states include some form of the emergency regime in their constitutional framework to enable a response to extraordinary circumstances (Bjørnskov and Voigt, 2016) also known as a state of emergency or state of exception (Gross, 2011). The types of extraordinary circumstances that states traditionally anticipate are natural disasters, armed conflicts, insurgencies, terrorist threats, and since recent economic crises (Gross, 2011; Rossiter, 2009; Ferejohn and Pasquino, 2004; Finn, 1990). These exceptional circumstances, as the opposition to the concept of normalcy (Gross, 2011), happen, by rule, abruptly (Scheuermann, 1996). They are temporal (Forejohn and Pasquino, 2004) and cause partial or complete suspension of the constitution while expanding executive powers (Gross, 2011). Finally, instruments and mechanisms designed to respond to the effect of emergencies are limited to the concept of emergency powers.

Related to this, the scope of emergency powers and misuse or even abuse of emergency powers are the traditional issues discussed around extraordinary circumstances (Bjørnskov and Voigt, 2016; Frankenberg, 2012; Gross, 2011; Ferejohn and Pasquino, 2004). This is also closely linked to the definition of sovereignty in which a sovereign is the one who gets to decide on the state of exception (Schmitt, 2005). Contemporary practices, however, bring new theoretical challenges to the concepts linked to extraordinary circumstances.

Maja Sahadžić

University of Antwerp

Antwerpen, Belgium

Almost half of the world’s population lives in multi-level systems, many of which experience identity differences. The identity differences, anyhow, are often seen as a contributory factor to extraordinary circumstances in multi-level systems (Watts, 2008;Burgess, 2006), as they induce fragmentation, threats, and crises that question the bare existence of the system (Obinger, Libfried, and Castles, 2005). This is because particular groups are likely to establish or maintain their own level of government, which competes with the traditional definition of sovereignty as described above (Sahadžić, 2017). In mild forms, risks include autonomy claims and claims for self-governance, while severe forms include self-determination, secession, independence claims, and separatism, accompanied by violence and even an armed conflict. One of the mild examples is certainly the Catalan referendum in 2017 while the most severe examples include the armed conflict in the former Yugoslavia from 1992 to 1995. To disable or settle the extraordinary circumstances, multi-level systems are prone to introducing asymmetrical constitutional solutions to accommodate identity differences (Sahadžić 2022; Sahadžić, 2021; Sahadžić, 2020a). Many examples around the world confirm that asymmetrical solutions in multi-level systems that exhibit elements common to identity differences are established under extraordinary circumstances: the 1995 Dayton Peace Agreement for Bosnia and Herzegovina that enabled the protection of three constituent peoples across two Entities, 10 cantons, and one district (with a similar process of drafting the constitution by foreign powers in Iraq), separate bilateral negotiations between the Chinese government and colonial powers over Hong Kong and Macau, the 1946 Gruber-De Gasperi Agreement that enabled the protection and a wide scope of autonomy of the German-speaking community in South Tyrol in Italy, the accession of Jammu and Kashmir to India, the so-called Good Friday Agreement between the British and Irish governments, and many more (Sahadžić, 2020a).

The identity differences often contribute to extraordinary circumstances in multi-level systems, as they induce fragmentation, threats, and crises that question the bare existence of the system. This is because particular groups are likely to establish or maintain their own level of government, which competes with the traditional definition of sovereignty.

There are, however, major differences in how extraordinary circumstances in contemporary multilevel systems affect the setup of emergency regimes. Certainly, a comprehensive discussion about the topic lies beyond the scope of this post, however, this is a starting point in readdressing the complex dynamics behind exceptional circumstances and adjusting the theoretical framework to better fit contemporary practice. One direction is to look into the differences in effects among the traditional types of risks and the risks caused by multinationalism.

Unlike the traditional extraordinary circumstances, contemporary threats and crises linked to multi-level systems happen incrementally. The effects of traditional exceptional circumstances largely differ from the exceptional nature of circumstances stimulated by differences in identity causing the general pattern of threats and crises originating from differences in identity to take a different form. That is because multi-level systems with differences in identity exhibit dynamic processes of constant search for autonomy and counterbalancing tendencies (Hooghe and Marks, 2012). Added to this, the leverage to influence, the dynamics will depend on many sides feeding the threats or crises (Keating, 2002). This has the potential to disperse the tension across the system. Because of that, contemporary extraordinary circumstances, such as autonomy claims, do not always have the force of abruptly creating disorder. They rather build up across the period of time, slowly bringing the system to the point at which a government response is necessary.

In general, the whole process is a rather transitional process to a long-term new type of normalcy. Government responses to identity differences through the creation of constitutional asymmetries also exhibit specific dynamics. The entire process, actually, may be perceived as a transition from bargaining about potential changes within the constitutional system to a new type of normalcy established in order to resolve an emergency. The new type of normalcy will be established thanks to asymmetrical constitutional solutions meaning that a threat or crisis based on identity differences will culminate in a transition to an asymmetrical constitutional framework. As such, constitutional asymmetry will often, if not always, limit the possibility of restoring the previous state of affairs in the constitutional design. This means that the accommodation of differences will lead to rather lasting changes to the constitutional system as once they are established, constitutional asymmetries will need to be renegotiated in order to be eliminated. Also, returning the constitutional system to its previous state actually means transforming the system into a new type of normalcy, as the previous normalcy no longer exists (Sahadžić, 2020b).

Unlike the traditional extraordinary circumstances, contemporary threats and crises linked to multi-level systems, such as autonomy claims, build up across the period of time, slowly bringing the system to the point at which a government response is necessary. Therefore, the emergency response, in the light of differences in identity and constitutional asymmetry, should emphasize processes of incremental, transitional, long-term accommodation aimed at a new type of normalcy that implies interventions into constitutional texts.

Finally, contemporary extraordinary circumstances will cause changes in constitutional provisions to match the demands but they will cause no effect on the separation of powers. Just like in previous cases, when extraordinary circumstances driven by identity differences force constitutional asymmetries they will have a different type of effect on the system from traditional extraordinary circumstances. They will influence the changes in constitutional provisions since the asymmetrical constitutional design has to be constitutionally defined to have its effect. This will certainly change the layout of the state. However, this will not influence the separation of powers. Instead, the effect could occur in the splitting of powers between various levels of government or the introduction of additional levels of government (Sahadžić, 2020b)

Consequently, further study is suggested, with more focus on how identity differences and constitutional asymmetries interact with the concept of constitutional emergency regimes. Even then, one is for sure: a shift in the understanding of constitutional emergency regimes is required. Contemporary extraordinary emergencies are not only bound to armed conflict, rebellion, terrorism, or economic crisis. The emergency response, in the light of differences in identity and constitutional asymmetry, should emphasize processes of incremental, transitional, long-term accommodation aimed at a new type of normalcy that implies interventions into constitutional texts (Sahadžić, 2020b).

References and Further Reading

Bjørnskov, C., & Voigt, S. (2016). The Architecture of Emergency Constitutions.

Burgess, M. (2006). Comparative Federalism, Theory and Practice. London and New York. Routledge.

Ferejohn, J., & Pasquino, P. (2004). The law of the exception: A typology of emergency powers. International Journal of Constitutional Law, 2(2).

Finn, J. E. (1990). Constitutions in Crisis: Political Violence and the Rule of Law. Oxford University Press.

Frankenberg, G. (2012). Democracy. In M. Rosenfeld & A. Sajó (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Constitutional Law. Oxford University Press.

Gross, O. (2011). Constitutions and emergency regimes. In T. Ginsburg & R. Dixon (Eds.), Comparative constitutional law. Edward Elgar.

Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2012). Types of Multi-level Governance In H. Enderlein, S. Wälti, & M. Zürn (Eds.), Handbook on Multi-Level Governance. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Hueglin, T. O. (2013). Comparing federalism: Variations or distinct models? In A. Benz & J. Broschek (Eds.), Federal Dynamics: Continuity, Change, and the Varieties of Federalism. Oxford University Press.

Keating, M. (2001). So Many Nations, So Few States: Territory and Nationalism in the Global era. In A.-G. Gagnon & J. Tully (Eds.), Multinational Democracies (pp. 39-64). Cambridge University Press.

Obinger, H., Leibfried, S., & Castles, F. G. (2005). Federalism and the Welfare State: New World and European Experiences. Cambridge University Press.

Rossiter, C. (2009). Constitutional Dictatorship, Crisis Government in the Modern Democracies. Transaction Publishers.

Sahadžić, M. (2017). Constitutional asymmetry vs. sovereignty and self-determination. sui-generis.

Sahadžić, M. (2020a). Asymmetry, Multinationalism and Constitutional Law, Managing Legitimacy and Stability in Federalist States. Routledge.

Sahadžić, M. (2020b). The Constitutionalism of Emergency: The Case of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Beyond: Multinationalism Behind Asymmetrical Constitutional Arrangements. In R. Albert & Y. Roznai (Eds.), Constitutionalism Under Extreme Conditions, Law, Emergency, Exception. Springer.

Sahadžić, M. (2021). Constitutional asymmetry and equality in multinational systems with federal arrangements. In E. M. Belser, T. Bächler, S. Egli, & L. Zünd (Eds.), The Principle of Equality in Diverse States, Reconciling Autonomy with Equal Rights and Opportunities (pp. 36-61). Brill Nijhoff.

Sahadžić, M. (2022). Constitutional Asymmetries as an (In)effective Counterbalancing Tool in Protecting Territorial Self-Government? In F. Requejo & M. Sanjaume-Calvet (Eds.), Defensive Federalism, Protecting Territorial Minorities from the “Tyranny of the Majority”. Routledge.

Schmitt, C. (2005). Political Theology, Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty. University of Chicago Press.

Watts, R. L. (2008). Comparing Federal Systems. School of Policy Studies, Queen’s University by McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Copyright: © (2022) Maja Sahadžić