Second Generation Fiscal Federalism and Multi-Level Crisis Management

Drawing on the Public Health Protective Policy Index (PPI) and data from the COVID-19 pandemic, this article highlights how political dynamics—particularly elite collaboration and partisan alignment between central and regional governments—affect policy coherence and public health outcomes. The findings underscore that successful crisis response in federal systems depends not only on decentralization but also on the political integration of federal and regional elites. The “Second Generation Fiscal Federalism” (SGFF) presents a more nuanced understanding of how political dynamics shape fiscal outcomes. The emphasis is on recognizing that political actors—driven by electoral and political incentives—do not always act as benevolent planners. Instead, their actions are shaped by political considerations such as party systems, elite cooperation, and regional versus national interests.

Onsel Gurel Bayrali

Department of Political Science

Binghamton University (SUNY)

Onsel Gurel Bayrali

Department of Political Science

Binghamton University (SUNY)

The COVID-19 pandemic posed unprecedented challenges to global governance, demanding swift, coordinated responses from political authorities to mitigate its public health and economic impacts. Federal systems, with their division of powers among different levels of government, offer distinct advantages for crisis management compared to unitary systems (Shvetsova et al., 2020). However, these advantages rely on strong intergovernmental collaboration for effective crisis responses.

In multi-level governance, balancing accountability between federal and regional leaders is key (Rodden, 2011). When electoral incentives are aligned between these levels, policy coordination flows more smoothly. But when their interests diverge, collaboration suffers, leading to inefficient policies and uneven crisis responses across federal systems.

Traditional decentralization theories, dating back to Tiebout (1956), assume that decentralizing public services to sub-national units improves welfare outcomes. Many studies support the positive impact of decentralization on public services, particularly in education and healthcare (Barankay & Lockwood, 2007; Porcelli, 2014).

Federal systems, with their division of powers among different levels of government, offer distinct advantages for crisis management, but these advantages rely on strong intergovernmental collaboration for effective crisis responses.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic revealed that decentralization alone isn’t a panacea for crisis management. Fiscal decentralization, for example, can create problems like soft-budget constraints, where local governments expect central government bailouts due to political incentives. Federal governments, motivated by political gains, may provide financial aid that worsens fiscal mismanagement at the local level (Qian & Roland, 1998). As Sharma (2017) demonstrates in the case of India, ruling parties often strategically allocate discretionary grants to affiliated states, prioritizing partisan gains over broader public welfare. This dimension of partisan federalism also manifests in other ways, such as when regions governed by co-partisans are more responsive to macroeconomic challenges, while opposition-led regions may politically benefit from central government failures (Khemani, 2007).

Second Generation Fiscal Federalism acknowledges that political dynamics significantly shape the outcomes of decentralization. Politicians, driven by electoral and political incentives, do not always act as benevolent planners (Weingast, 2014). Rather, they often engage in pork-barrel politics, prioritizing short-term partisan gains and wasteful government expansion over long-term social welfare (Sharma 2017). However, federal systems are not inherently ineffective in crisis response. As Litvack et al. (1998) noted, the impact of decentralization depends on the institutional and political context. Sharma (2008, 2012) further emphasizes that the effectiveness of decentralization hinges on both the objectives policymakers aim to achieve—whether it is to bring government closer to the people or to split sovereignty between various levels—and how decentralization is designed, either through devolving revenue-raising powers or through funding via intergovernmental transfers.

Our research (Bayrali and Shvetsova, 2024; Bayrali, 2023, 2024; Bayrali and Jimale, 2024) emphasizes the critical role of party systems and the integration of political elites in this context. Integrated party systems—where central and regional elites collaborate—help stabilize federal structures by promoting political competition while safeguarding elite interests (Filippov, 2005; Ponce-Rodriguez et al., 2020). These systems encourage decentralization that supports democracy and leads to more effective crisis management and improved public services, especially in health and economic sectors during crises like COVID-19.

In an integrated party system, parties create an interdependent relationship among elites under a unified party umbrella. Local politicians recognize the benefits of their local positions being enhanced by the party’s national brand, while national politicians understand the value of local party organizations in securing votes to maintain office (Filippov et al., 2004). This interdependence fosters elite coordination, making party elites mutually accountable and strategically aligned.

In such systems, politicians tend to prioritize electoral gains over representing their narrow constituencies. Broad political parties play a crucial role in coordinating these mainstream politicians across various jurisdictions, ensuring the stability of federal institutions (Filippov et al., 2004). This cooperation allows central and local incumbents to collaborate in policymaking, minimizing policy failures across government levels.

A New Tool: The Public Health Protective Policy Index

Our research uses the Public Health Protective Policy Index (PPI), a dataset capturing central and local governments’ non-medical policy interventions during the pre-vaccine phase of COVID-19 at the sub-national level. Developed by the Binghamton University COVID-19 Lab, the dataset covers 17 constitutional federal countries and 418 jurisdictions in 2020, tracking daily public health policies across categories like border and school closures, regulations of public spaces, and local economic activities (Shvetsova et al., 2022).

This dataset provides three indices that assess the policy performance of government units: National PPI (central authority measures), Regional PPI (regional authority measures), and Total PPI (the most stringent policies implemented by either authority). These indices offer insights into both absolute and relative policy performances, allowing researchers to evaluate which level of government was more active in policy interventions.

While these indices measure absolute policy efforts, the ratios of Regional PPI to Total PPI and National PPI to Total PPI reveal the relative policy burden on each level of government. The values, ranging from 0 to 1, reflect the degree of stringency, providing a window into how crisis management is handled across different jurisdictions.

Empirical Insights: Linking Integrated Party Systems to Public Health Policy Performance

The PPI index offers the flexibility to assess both the absolute and relative policy performances of central and regional governments at the sub-national level. Regional PPI or National PPI reflect the absolute policy efforts of local and central governments, respectively, while Regional PPI/Total PPI indicates the extent to which regional governments are shouldering the crisis management burden.

To evaluate whether a sub-national party system is integrated, we analyze the total vote share of regional parties in state elections. The strength of these parties serves as a signal to federal politicians about how state-level policies could influence national politics. In less integrated systems, where regional parties dominate, the focus on local issues can weaken policy coherence, reducing the incentive for collaboration between central and local elites.

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed that decentralization alone isn’t a panacea for crisis management, as political dynamics significantly shape the outcomes of decentralization

We include both de facto regional parties, which primarily join elections within a single administrative region, and de jure regional parties, officially labelled by national electoral commissions. These parties may participate in both local and national elections in different states but are influential in one region, allowing us to capture both regionally dominant and nationally active parties with localized power.

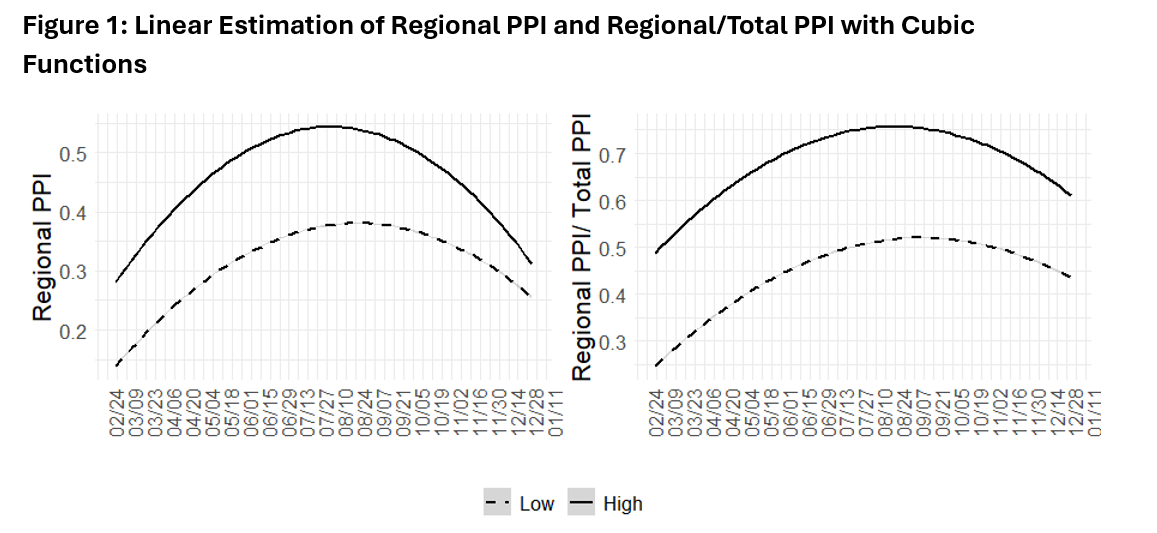

Figure 1 illustrates the linear estimates of Regional PPI and Regional PPI/Total PPI over time in 2020. Regions with a high vote share of regional parties (above 50%) are compared to regions with a lower share. The graph on the left shows the absolute policy burden of regional authorities, while the graph on the right demonstrates the relative policy burden. The estimates suggest that as regional parties gain influence, federal authorities tend to shift more blame onto regional authorities in both absolute and relative terms.

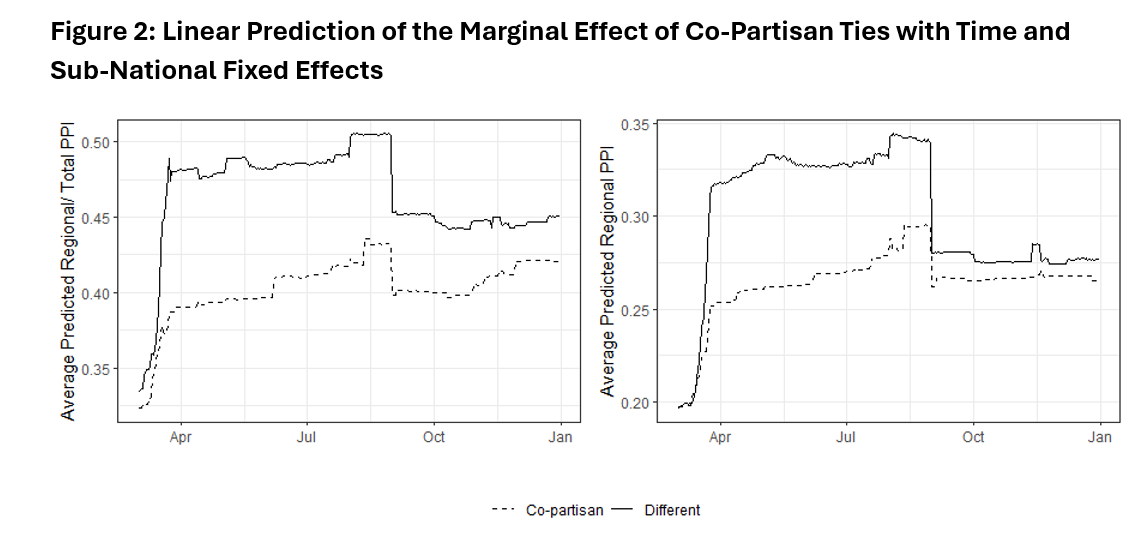

Figure 2 shows the negative impact of the interaction between partisan alignment and regional party vote shares on the policy burden experienced by regional authorities. Using linear predictions with time and sub-national fixed effects, the figure reveals that co-partisan regional governments with similar electoral power of regional parties bear less policy burden compared to other regions, though this gap narrows when examining absolute policy performance.

Integrated party systems, where central and regional elites collaborate, help stabilize federal structures by promoting political competition while safeguarding elite interests. Therefore, Successful crisis management in federal systems depends not only on delegating policies to sub-national units but also on the political integration of federal and regional elites.

In short, the COVID-19 pandemic has shown that successful crisis management in federal systems relies not only on delegating policies to sub-national units but also on political dynamics. Integrated party systems, where local and national politicians collaborate effectively, enhance policy coherence and crisis response. Tools like the Public Health Protective Policy Index offer valuable insights into how these systems influence public health outcomes, helping us better understand and improve multi-level governance in future crises.

REFERENCES

Barankay, I., & Lockwood, B. (2007). Decentralization and the productive efficiency of government: Evidence from Swiss cantons. Journal of Public Economics, 91(5-6), 1197–1218.

Bayrali, O. G. (2023). Center-Regional Political Risk Sharing in the COVID-19 Public Health Crisis: Nigeria and South Africa. In Government Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Between a Rock and a Hard Place (pp. 107-125). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Bayrali, O. G. (2024). Party System Dynamics and Intergovernmental Collaboration: Exploring the Impact of Regional Parties on COVID-19 Policies in Federal Systems. (Working Paper). Binghamton University.

Bayrali, O. G. and Jimale, A. (2024-Forthcoming). Covid-19 Pandemic in Somalia, South Africa and Zimbabwe: Why do leaders love COVID-19 precautions? Covid 19 and Public Policy: Contributions to Conflict Management, Peace Economics and Development. Emerald Publishing.

Bayrali, O. G. and Shvetsova, O. (2024). Public health as a public good: Optimal production in COVID-19 pandemic? (Working Paper). Binghamton University.

Filippov, M. (2005). Riker and federalism. Constitutional Political Economy, 16, 93–111.

Filippov, M., Ordeshook, P. C., & Shvetsova, O. (2004). Designing federalism: A theory of self-sustainable federal institutions. Cambridge University Press.

Khemani, S. (2007). Does delegation of fiscal policy to an independent agency make a difference? Evidence from intergovernmental transfers in India. Journal of Development Economics, 82(2), 464–484.

Litvack, J. I., Ahmad, J., & Bird, R. M. (1998). Rethinking decentralization in developing countries. World Bank Publications.

Ponce-Rodríguez, R. A., Hankla, C. R., Martinez-Vazquez, J., & Heredia-Ortiz, E. (2020). The politics of fiscal federalism: Building a stronger decentralization theorem. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 32(4), 605–639.

Porcelli, F. (2014). Electoral accountability and local government efficiency: quasi-experimental evidence from the Italian health care sector reforms. Economics of Governance, 15, 221–251.

Qian, Y., & Roland, G. (1998). Federalism and the soft budget constraint. American Economic Review, 1143–1162.

Rodden, J., & Wibbels, E. (2011). Dual accountability and the nationalization of party competition: Evidence from four federations. Party politics, 17(5), 629–653.

Sharma, Chanchal. K. (2009). Emerging dimensions of decentralisation debate in the age of globalisation. Indian Journal of Federal Studies, 19(1), 47-65. Hamdard University.

Sharma, Chanchal. K. (2012). Beyond gaps and imbalances: Re-structuring the debate on intergovernmental fiscal relations. Public Administration, 90(1), 99-128. Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Sharma, Chanchal. K. (2017). A situational theory of pork-barrel politics: The shifting logic of discretionary allocations in India. India Review, 16(1), 14-41.

Shvetsova, O., Zhirnov, A., VanDusky-Allen, J., Adeel, A. B., Catalano, M., Catalano, O., … & Zhao, T. (2020). Institutional origins of protective COVID-19 public health policy responses: informational and authority redundancies and policy stringency.

Shvetsova, O., Zhirnov, A., Adeel, A. B., Bayar, M. C., Bayrali, O. G., Catalano, M., . . . others (2022). Protective policy index (ppi) global dataset of origins and stringency of covid 19 mitigation policies. Scientific data, 9(1), 319.

Tiebout, C. M. (1956). A pure theory of local expenditures. Journal of Political Economy, 64(5), 416–424.

Weingast, B. R. (2014). Second generation fiscal federalism: Political aspects of decentralization and economic development. World Development, 53, 14–25.

© Author