Nepal’s intergovernmental Collaboration during the Covid-19 Pandemic

Abstract

As one of the newest federal countries, Nepal’s intergovernmental collaboration in dealing with the adverse impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic (2020/21) needs special attention. In the absence of clarity in the roles of federal, provincial, and local governments in the management of such an unanticipated public health crisis, it appeared in the first few months of the pandemic that each level of government functioned rather inwardly. Consequently, preliminary efforts of providing shelter and food to save lives remained ineffective. In response to this remarkably failed circumstance, the government of Nepal introduced new collaborative measures that leveraged engagement of federal, provincial, and local governments in harmoniously providing medical help and other daily needs to citizens. This conference paper examines these measures to understand the degree to which the COVID-19 pandemic generated needs to strengthen intergovernmental collaboration in Nepal.

Thaneshwar Bhusal

Honorary Professional Associate

Centre for Change Governance

University of Canberra, Australia

Starting immediately on 24th March 2020, the federal government of Nepal declared a nation-wide closure of business, non-essential government services, all forms of endogenous and exogenous mobility, and international border, following just two positive incidents of coronavirus out of 610 randomly tested suspected cases. The declaration interrupted daily life in mass, with hundreds of thousands of Nepali people facing job loss, generating food crisis, and thus obstructing their regular routines. The economic damage of the move is still to be known, although the annual economic growth plummeted to -2.1% in 2020, and 2.7% in 2021, which was 6.7% in 2019, and 7.6% in 2018 (Ministry of Finance, 2022). A small volume of research on the adverse impact of national lockdown on sectoral policy areas such education (Tulza, 2020), public health (Sharma et al., 2021) and local governance (Bhusal, 2020) is there, yet we do not know much about the impact of COVID-19 on the efficacy of intergovernmental collaboration designed after the promulgation of new federal constitution in 2015.

This research is an attempt to bridge this knowledge gap. Based on the secondary sources of information, and their discursive interpretation, it aims to understand how far intergovernmental collaboration was managed to defeat the adverse social and economic impacts of COVID-19. After this introduction, it briefly discusses collaborative governance literature to understand how intergovernmental relations can facilitate collaboration among different levels of the government in federal settings. In the third part of this paper, it brings Nepal’s Constitution (2015) as a starting point to understand the federal institutional design in which a range of public sector organisations of federal, provincial, and local governments hinge. In the fourth section, a thorough explanation of how governments at different levels collaborated in policymaking and service delivery arrangements during the peak times of COVID-19 between 2020 and 2021. The discussion section analyses the implications of the collaborative arrangements. Finally, the paper concludes with reflection of collaborative intergovernmental relations in Nepal.

The political domain of collaborative governance is relatively ambiguous in Nepal, as political parties do not function in accordance with the principles of federalism.

The collaborative governance literature

The conventional domain of exercising collaboration is at the intersectional spaces of government organisations at horizontal and vertical arenas. Unitary systems devise collaborative mechanisms horizontally to establish functional relations between central government agencies and subnational government entities. Decentralised polities, on the other hand, design collaboration vertically to enable joint works to be carried out by and between subnational governments. It is therefore asserted that a decentralised environment is more conducive than other systems of government to flourish collaborative governance (Emerson et al., 2012). The federal system of government – one of the most favourable systems of decentralisation – therefore requires devising extensive mechanisms for both vertical and horizontal coordination mechanisms to be implemented across different levels of government viz. federal, state/provincial, and local. As time progressed, so did our understanding of how governments began to, and should, collaborate with actors of governance beyond the executive branch of government (World Bank, 1997). This new paradigm in collaborative governance means that governments must expand collaborative opportunities with the public, i.e. private sector and the not-for-profit sector (Bingham, 2011: 387).

Three pertinent questions of collaborative governance need to be clarified (Ansell et al., 2017). The first is the question of why and when governments need collaboration. If the trajectory of public administration is transcending toward public governance through new public management, then the answer to ‘why and when to collaborate’ questions heavily rely upon the theories of neoliberalism, which – among other things – advocate for the government being a rower, not a steerer (Osborne, 2006). This new landscape of governance is naturally demanding to collaborate with a range of stakeholders in delivering public services, while maintaining only the sovereign power of policymaking with the government.

The second question relates to the notion of partners i.e. whom should the government be partnering with, particularly in relation to implementing certain policies. The private sector aims to collaborate only if it sees profits in the venture (Emerson et al., 2012). It is therefore the responsibility of the government to create a conducive atmosphere to generate profit if the private sector is expected to collaborate with the government. Partnering only with a profit-making regime does not necessarily produce the elements of collaborative governance. It is the World Development Report (1997) that reinvigorated the need to define governance in the triangular shape, placing the government at the top, private sector at the left, and the civil society/non-governmental sector at the right (World Bank, 1997). This definitional revitalisation has certainly opened spaces for the not-for-profit sector to partner with the government in delivering services, although modern governments seem to be maximising the partnership with this sector in other processes of government such as policymaking.

“What is the method or mode or approach to collaborative governance?” is the third question that needs clarifications. Conventionally, the government would develop performance measures and output indicators to govern the contract between actors (Halligan, 2020). Such a contract would work as the fundamental method to implementing collaborative governance mechanisms. Collaborative governance in recent times has witnessed significant changes, innovations, and thus extensive engagement of actors, all of which have revitalised collaboration methods, modes, and approaches (Bevir, 2011).

Institutions for collaborative governance in Nepal

The Constitution of Nepal (2015) institutionalises federalism as a way of organising collaborative governance at the federal, provincial, and local level, and also between three levels of government. Each level of government is empowered with constitutionally arranged functions, with adequate avenues for intergovernmental collaboration in policymaking and implementation. Appropriate resources are also devised in the constitution that guarantee inter alia tax sharing and formulae-based grant distribution across jurisdictions (National Natural Resources and Fiscal Commission, 2019). The constitutionally devised intergovernmental institutions offer reasonable spaces for political, financial, and administrative collaboration. The political domain for collaborative governance is relatively ambiguous, as political parties do not seem adequately transformed in accordance with the principles of federalism in Nepal (Bhatta, 2022). Despite an ambiguous political landscape in terms of implementing collaborative governance, the notion of political autonomy in the policymaking process has been remarkably maintained in the constitution, which political parties cannot underestimate regardless of their political manifesto. The highest-level political institutions to assure collaborative atmosphere include intergovernmental and intra-governmental coordination councils, respectively chaired by the Prime Minister and provincial premiers. The federal planning commission and provincial policy commissions are subsets of the high-level political entities that frame collaborative policy regimes across federal, provincial, and local government level. At the intersection of all federal units, the District Coordination Committees (DCCs) provide genuinely functional political spaces – albeit their limitations – to exercise collaborative governance at the local level (Bhusal, 2022).

The financial domain for collaborative governance in Nepal has been analysed as a controversial subject for some time, although such contestation has not emerged only from the institutional design of federalism (Khanal, 2016). At the federal level, the provision of National Natural Resources and Fiscal Commission (NNRFC) is authorised to prescribe a formula-based grant system, which the Ministry of Finance must follow while making annual budgets. While the fundamental source of such formulae is the constitution itself, the NNRFC may develop additional criteria to allocate grants to be awarded to federal, provincial, and local governments. Four diverse types of financial grants are covered in the National Natural Resources and Fiscal Commission Act (2017) and Intergovernmental Financial Management Act (2017): federal equalisation grant, conditional grants, complementary or matching grants, and special grants. The financial domain – as seen in the collaborative governance regime – thus plays a crucial role in ensuring funding for collaborative governance, with possibilities to encourage jurisdictions to generate collaborative projects (Dhungana and Acharya, 2021).

Then comes administrative space which has been considered to have less significance in theory but has evolved as the most effective tool for collaborative governance in practice, particularly in the Nepalese context (Smith et al., 2022). The institutional provision of the National Public Service Commission (NPSC) at the federal level is an assurance of providing most competent human resources to the federal government only. Provincial governments are also equipped with a power to have their own Provincial Public Service Commissions (PPSC) to recruit human resources for provincial and local governments. As the constitution envisions the federal parliament to provide a national framework to both NPSC and PPSC, it has not happened during the whole period of first five-year tenure of federal parliament. Consequently, provincial and local governments faced severe human resource crisis although an interim legislation of the federal government helped partially address the crisis (Government of Nepal, 2019). In absence of complete and competent human resources, the research witnesses that public administration appeared to have less supportive in flourishing collaborative governance in Nepal.

The bright side of the pandemic management is that, by the time the second wave emerged, each level of government started realising their constitutionally guaranteed roles, rights, and responsibilities.

An outlook of pandemic management in Nepal

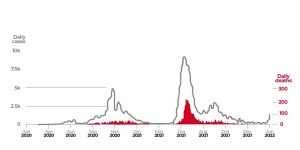

This section describes how different levels of government worked together through political, financial, and administrative tools during the most difficult times caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in Nepal. Two major waves of COVID-19 pandemic are taken in this conference paper as subjects of analysis, although some preludes and epilogues of these two peaks complement the inquiry (Figure 1). The analysis primarily considers governmental interventions, recognising the active presence of nongovernmental actors in the management of adverse impact of the pandemic.

With the declaration of nationwide lockdown by the federal government on 24th March 2020, there appeared a misty highway where governments at all the three levels had to drive their relief, rehabilitation, and rescue (RRR) vehicles at full speed. Although the government’s decision to impose a nationwide lockdown was implicitly rooted in the Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act 2017, the absence of policy clarity created havoc in the working of public sector organisations, generating massive public frustration in the management of such suddenly appeared yet ill-prepared notion of public health crisis. The federal government’s response to the pandemic echoed some of the best-known international practices – particularly in neighbouring India did work a little, yet mobility restrictions of ordinary people and closure of international borders and airports severely damaged public trust in the government’s actions.

Figure 1. COVID-19 waves in Nepal

Source: Nepali Times, Published January 13, 2022.

At some point in time, the federal government led the entire RRR functions, considering the Constitutional mandate to handle public health crisis like COVID-19. With the promulgation of several bylaws and directives alongside of a few fringe cabinet decisions, the federal government established a dedicated paramilitary entity called the COVID-19 Crisis Management Centre (CCMC). The Centre was given an unimagined scale of regulatory power to inter alia oversee international borders, including airports, interprovincial mobility of people, and issuance of no objection letters for emergency movements. By the end of July 2020, it became a norm that the Cabinet would sit only to endorse decisions recommended by the CCMC.

The simple interpretation of the role of CCMC, and other influential federal government entities such as the Ministry of Health and Population during the first lockdown period between March and July 2020 paints an ambiguous picture of how governments at three levels worked together. At the outset, the federal government steered almost all the RRR activities. Almost all the federal public sector organisations were closed, affecting the delivery of public services. The core of the pandemic management, however, was thoroughly handled by provincial and local governments albeit their limitations in resources, authority(?), and interprovincial and interlocal coordination. As the lockdown period was being extended every fortnight by the federal government, public trust with the federal government was gradually decreasing, which provided an opportunity to provincial and local governments to step up in providing essential services to the communities (Sharma et al., 2021).

The most vulnerable group of people to the lockdown appeared Nepali migrant workers stranded overseas. Hundreds of thousands of Nepali citizens stuck in the foreign land with thousands of people queuing in front of Nepali embassies to return home. Amidst the cancellation of almost all international airlines, the plight of migrant workers to get to home could not be appropriately heard neither by Nepali diplomatic missions abroad nor any level of government back home. Although the federal government promulgated a guideline to provide rescue and rehabilitation support to stranded migrant workers, the efficacy of such guideline is still questioned as reaching out to needy migrant workers with cash or other forms of support remained the most challenging task (International Organisation for Migration, 2021; Migrant Forum of Asia, 2020).

With the emergence of the second wave of COVID-19 pandemic in April 2021, the government seemed to have learned several strategies from their experience of the first wave. The official data suggests that Nepal entered the second wave of the public health crisis in April which lasted for nearly three months. While the health impact with rising death tolls during the second wave remained far more alarming than the first, the management side appeared relatively satisfactory because the federal government devolved many of the functions to subnational entities owned by provincial and local governments. By the time the second wave emerged, many local and provincial governments were found to have better prepared to combat the virus with public health, economic, and social tools explored and advanced during the first wave of the pandemic.

During the second peak of the pandemic, most of the CCMC roles explored, developed, and codified in the interim legislation during the first lockdown were devolved to local governments. The local governments not only reinvigorated their constitutionally defined functions but also implemented strategies according to their contexts. This way, the entire COVID-19 induced pandemic management techniques diversely evolved across local governments, many of which were replicable to other similar localities. Although comprehensive research would require reaching to any conclusion, the local government strategies to defend the adverse impact of the second wave of the pandemic were astonishingly innovative, and thus people were comparatively satisfied. The primary functions performed by local governments under the devolved jurisdiction of CCMC – named as Local-level Crisis Management Centre (LCMC) were related to providing immediate relief to poor, needy, and most affected people, developing shelter houses and isolation centres, and delivering food, goods, and services to the starving populace.

Regardless of the devolved institution of the CCMC and the new management dynamics shown during the second wave of the pandemic, the role (and responsibilities) of provincial governments remained unclear. It is evident in many of the official publications of provincial governments that they worked closely with local governments in providing necessary financial resources, among other things, to complement local governments’ relief and rehab initiatives. Some provincial governments also established isolation centres to host infected people with the hope of providing dedicated treatment, yet such centres had to align with local governments’ strategies. In other words, the provincial governments’ role remained confusing during the second wave of COVID-19 pandemic in Nepal.

Discussion

Several lessons were learned when governments at different levels played diverse roles during the first and second peaks of the COVID-19 pandemic in Nepal. While each lesson may have its own implication to the studies of varieties of fields within the public administration discipline, this research picked lessons for collaborative governance scholarship. The proposition is that Nepal’s experience of intergovernmental collaboration during crisis times may offer crucial insights into the studies and practices of federalism in crisis, which perfectly links with the theme of the conference. This section interprets the case by keeping analytical components presented in the literature review section above.

Three key messages are discussed as they expand the existing understanding of intergovernmental collaboration in federal settings. The first message refers to the notion of how federal units co-worked both horizontally and vertically during the first and second lockdown periods. As described above, the first lockdown period exclusively witnessed the overarching role of the federal government in handling the management of the pandemic. Efforts of the federal government seemed thoroughly top-down, generating questions over the constitutional aim of empowering subnational entities in policymaking and service delivery. The paramilitary entity at the federal level certainly thwarted the democratic spirit of Nepal’s federal constitution and thus challenged the capacity of public administrators of the federal government. The horizontal notion of collaborative governance remained constrained as the CCMC continued to underestimate public health advice of the Ministry of Health and Population, among others. Coordination with military and police force seemed harmonised, yet the question of the justification of their presence in public service delivery remains unanswered.

The second message of the intergovernmental collaboration during COVID-19 pandemic refers to the extent to which each level of government was empowered to cooperate with nongovernmental actors. This scenario appeared only after a trial of the first lockdown in 2020. The first lockdown period did not envision to include nongovernmental actors in any of the RRR efforts. However, the evolving reports of many of the nongovernmental actors suggest that they aimed to reach out to needy people during those lockdown periods with cash, food, and other medical help (KC, 2022). Research also indicates that some local governments continued to collaborate with communities in the making of annual budgets and programs, although such power was not necessarily devolved by any federal entity but the Local Government Act (2017) had already codified it (Bhusal, 2020). The third lesson of Nepal’s experience in the implementation of intergovernmental collaboration refers to the notion of the efficacy of provincial governments in offering collaborative governance. Although Nepal’s federalism is still in its prematurity, there is a growing critique of provincial governments as most of the provincial governments have not been able to justify their rationale (Bahl et al., 2022). In recent times, political parties are also quoted as expressing their disbelief in the provincial structure of Nepal’s federalism, posing serious threats to dismantle or defunct provincial governments (Breen, 2022). It seemed that the pandemic had given provincial governments a chance to increase public trust in their institutions and or processes, but they failed. As their institutional design permits, weaknesses learned during the management of COVID-19 pandemic may provide insights for future reforms to reinvigorate provincial governance in Nepal.

Conclusion

This conference paper endeavoured to empirically interpret Nepal’s efforts to combat COVID-19 pandemic, specifically in line with her recently promulgated federal constitution. It considered two instances of lockdown periods in 2020 and 2021 – which are also commonly known as first and second waves of the pandemic. While the governmental effort to beat the virus is still ongoing, the discussion of the incidents happening at federal, provincial, and local level produce some exciting and a few disappointing insights to the studies and practices of collaborative governance. The bright side of the pandemic management is that, by the time the second wave emerged, each level of government started realising their constitutionally guaranteed roles, rights, and responsibilities. Many local governments in particular showcased their capacity, innovativeness, and leadership in providing RRR with long-lasting implications to local democracy and local governance (see Bhusal and Acharya, forthcoming). A relatively disappointing notion is the performance of provincial governments. Despite their conducive institutional design to collaborate with federal government upward and local governments downward, many provincial governments lacked capacity to design collaborative projects in crisis times. The efforts of provincial governments in defending the virus remained largely unnoticed – if there were any, which fuelled critics to raise their voices against provincial structure. There is obviously some form of organisational vacuum at the local level which causes provincial governments to actively reach out to communities, yet the possibility to collaborate with local governments, and thus local communities was not exhumed innovatively.

The research thus reaches to a conclusion that the pandemic has generated needs to expand intergovernmental collaboration, with clear roles and responsibilities of each level of government. Federal government should continue to develop collaborative policy frameworks; the provincial government must be innovative and supportive for strong local democratic institutions; and, local governments must always be open to launch as many collaborative projects as possible. In doing so, local governments must not forget to collaborate with local communities, nongovernmental organisations, and the private sector whenever possible. The bigger the size of such collaborative projects becomes, the more the upper-level governments should step up and lead the projects.

References

Ansell C, Sørensen E and Torfing J (2017) Improving policy implementation through collaborative policymaking. Policy & Politics 45(3): 467-486.

Bahl RW, Timofeev A and Yilmaz S (2022) Implementing federalism: The case of Nepal. Public Budgeting & Finance 42(3): 23-40.

Bevir M (2011) The SAGE Handbook of Governance. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Bhatta CD (2022) Rooting Nepal’s Democratic Spirit. Kathmandu, Nepal: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

Bhusal T (2020) Citizen participation in times of crisis: Understanding participatory budget during the COVID-19 pandemic in Nepal. ASEAN Journal of Community Engagement 4(2): 321-341.

Bhusal T (2022) Understanding local government coordination: An assessment of District Coordination Committees in Nepal. State and Local Government Review 54(1): 68-81.

Bingham LB (2011) Collaborative Governance. In: Bevir M (ed) The SAGE Handbook of Governance. London: SAGE Publishing House, pp.386-401.

Breen M (2022) Political parties in federalism in Asia. In: Science Blog. Available at: https://www.eurac.edu/en/blogs/eureka/political-parties-in-federalism-in-asia.

Dhungana RK and Acharya KK (2021) Local government’s tax practices from a cooperative federalism perspective. Nepal Public Policy Review 1: 157-178.

Government of Nepal (2019) Public Personnel Adjustment Law. Kathmandu: Nepal Law Books Management Committee.

Halligan J (2020) Reforming public management and governance : impact and lessons from Anglophone countries. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

International Organisation for Migration (2021) Migration & Socio-Economic Impact of COVID-19: Assessment of Return Communities in Nepal. Nepal: International Organisation for Migration,.

KC D (2022) COVID-19 and non-governmental organisations in Nepal. Voluntary Sector Review 13(2): 1-11.

Khanal G (2016) Fiscal Decentralization and Municipal Performance in Nepal. Journal of Management and Development Studies 27: 59-87.

Migrant Forum of Asia (2020) Migration and Inclusive Democracy: Impact of COVID-19 in Asia. Manila: Migrant Forum of Asia.

National Natural Resources and Fiscal Commission (2019) First Annual Report, 2019. Reportno. Report Number|, Date. Place Published|: Institution|.

Osborne SP (2006) The New Public Governance? Public Management Review 8(3): 377-387.

Sharma K, Banstola A and Parajuli RR (2021) Assessment of COVID-19 Pandemic in Nepal: A Lockdown Scenario Analysis. Front. Public Health 9.

Smith RB, Smith NN and Safarin MHAF (2022) Federalism and Regional Autonomy: Overcoming Legal and Administrative Hurdles in Nepal and Indonesia. Lex Scientia Law Review 6(1).

Tulza K (2020) Impact of covid-19 on university education, Nepal. Tribhuvan University Journal 35(2): 34-46.

World Bank (1997) World Development Report 1997: the state in a changing world. Oxford University Press.

To cite:

Bhusal, T. (2022). Nepal’s Intergovernmental Collaboration during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Conference Proceeding presented at the Hans Seidel Stiftung (HSS) Conference on Federalism in Crisis Times. New Delhi: Central University of Haryana.

Copyright: © (2022) Thaneshwar Bhusal