Partisanship and the Separation of Powers as Predictors of Public Health Restrictions

Federal systems face inherent challenges when mobilizing to meet the demands of crisis due to the immense coordination challenges faced by autonomous federal and state governments. The American federal system relies on cooperation between the federal government, playing a crucial role in financing state responses, and state governments, that have broad authority over public health. Public health crises, like COVID-19, demand executive action to declare an emergency, coordinate resources vertically from federal to state to local governments, horizontally across the bureaucracies of government, and delegate responsibility to specialists that can advise governments at all levels what policy actions must be taken to protect the public.

The COVID-19 pandemic represents an opportunity to evaluate the robustness of the American federal system and its public health policy response. State-level institutions have been brought to the forefront because normally cooperative intergovernmental relations degenerated into transactional federalism. American governors, each state’s primary executive authority, became critical actors because of the institutional tools at their disposal to respond to the pandemic. State-level responses were far from uniform, lacked a coherency that would normally harmonize policies across the system, and ultimately led to the deaths of 345,323 Americans during the first year of the pandemic alone.

William M. Myers

University of Tampa, Florida

The sudden onset of a disaster or crisis lends itself to the exploration of the effects of institutions and varying institutional arrangements that characterize state-level government across the United States. The most fundamental is that of the separation of powers between the executive and legislative branches and its partisan dimensions. The specter of divided government haunts not only the United States federal government, but its fifty state governments as well. It is in this shadow that the public health policy responses of the American states are evaluated.

Federal systems face inherent challenges when mobilizing to meet the demands of public health crises due to the immense coordination challenges required for successful cooperation between governments with distinctive decision-making authority. American governors became critical actors because of the institutional tools at their disposal and the breakdown of intergovernmental relations. State-level responses were far from uniform and lacked a coherency that would normally harmonize policies across the system.

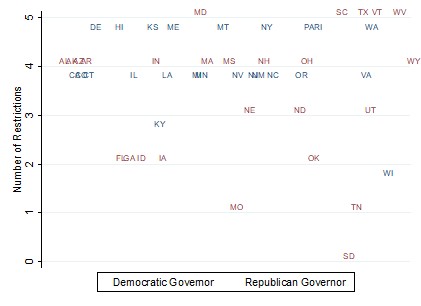

The first year of the pandemic was an environment characterized by a great deal of uncertainty and a reliance on public health interventions to mitigate the viral spread of COVID-19. Vaccine development, let alone trials and authorization for use, were a dream. Public health policy recommendations instead relied on hand washing, social distancing, travel restrictions, school closures, lockdowns, quarantines, mask mandates, and restrictions on businesses and socializing. America’s governors had several tools to select from and I focus on five public health policy restrictions: stay-at-home orders, quarantines for people entering the state, and mask mandates for the general public, for businesses, and in schools. The figure below counts how many of these restrictions were put into force by a state’s governor as a state-wide mandate during the 2020 calendar year. Most states implemented most if not all these restrictions. However, there is a clear partisan dimension to these decisions, with Republican Governors from eleven states ordering three or fewer restrictions compared to two Democratic Governors.

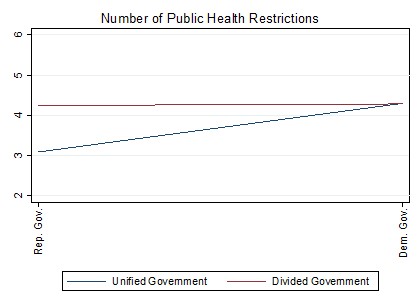

The decision by state governors to implement any public health restriction did not go unchallenged in states with divided governments. The legislatures of Wisconsin and Michigan sued their respective governors in state courts seeking to prevent the executive’s broad use of emergency powers. These episodes highlight the importance of the separation of powers between the executive and legislative branches in politically divided states. The figure below graphs the joint effect of divided (unified) government on Democratic (Republican) Governors and their likelihood of implementing the cumulative count of public health restrictions. The blue line represents unified government and the red line divided government. Republican unified governments are much less likely than other combination of governments and partisanship of the governor to adopt health restrictions. Under divided governments, whether with a Republican Governor or Democratic Governor, the probability of adopting increasing numbers of health restrictions does not change. Democratic unified governments approach the number of restrictions expected under a divided government.

Whether the government is unified or divided, the extent of executive order authority and the legislative override threshold may all be colored by the partisan view of the appropriate use of power regardless of the authority granted or the gravity of the moment.

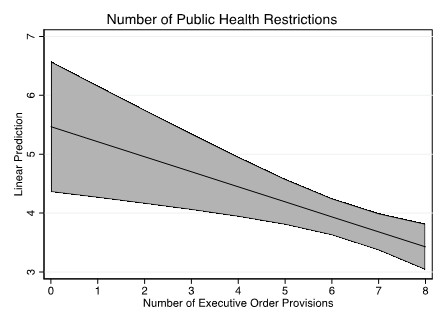

State governors’ decisions to implement increasing numbers of restrictions was also conditioned on two additional institutional factors: the breadth of executive order power and the percentage of the legislature required to override a gubernatorial decision. America’s governors employ executive orders as a means to either act unilaterally without interference from the legislature or as a means of expediting delegated authority. Governors have deployed executive orders across a wide array of policy areas from workplace discrimination to the operation of state agencies to natural disasters to infectious disease emergencies. Many governors, though not all, have wide discretion to act unilaterally across a variety of policy areas.

The figure below indicates that governors with expansive authority to issue executive orders were less likely to do so with respect to public health restrictions. Governors with less discretionary authority were more likely to enact higher numbers of restrictions, not fewer. Governors with seemingly fewer tools available to them in a crisis were willing to use them whereas governors with extremely broad authority were less likely to take advantage of their position.

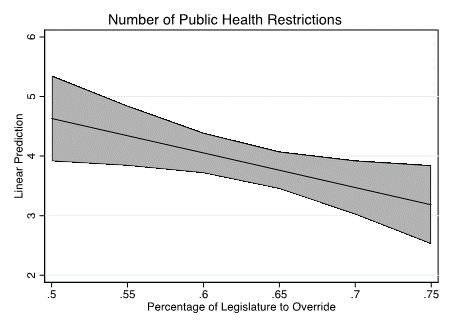

Governors are part of a separation of powers system that permits the state legislature from overriding their decisions. The figure below indicates that governors were more likely to adopt public health restrictions the lower the legislative override threshold was or conversely were less likely to issue such restrictions as the threshold increased.

The figures regarding executive order provisions and legislative overrides together provide evidence that suggests governors who have been given a wide latitude of authority and are insulated in the use of that authority are less likely to use it to, in this case, protect public health through the adoption of restrictive mitigation measures meant to stop the spread of the disease. At a time when America’s governors were debating what they could do to protect public health through restrictive public health measures, many of those executives with the power to do more chose not to. Institutions incentivize behavior, but the delegation of authority to act does not necessarily result in action.

When we assemble the results discussed above, it is important to consider what the institutional and partisan context of states means for the American federal system’s ability to navigate a future public health crisis. The findings suggest that state institutional arrangements affect how American governors deploy their powers in response to a public health emergency. Whether government is unified or divided, the extent of executive order authority, and the legislative override threshold may all be colored by the partisan view of the appropriate use of power regardless of the authority granted or the gravity of the moment.